6am wake-ups. 7.30am school bells. Classes till 2pm. CCAs till 6pm. Dinner, tuition, homework, and finally, sleep. Sound familiar? It should. It was my typical weekday growing up, and probably yours too.

Now, at 23, I look back in disbelief. How did we function on so little rest, with so much to do? There were days I barely remembered what I had learned. But the routine was so entrenched that I didn’t question it. No one around me did either. But mounting evidence shows that what felt normal was in fact detrimental to us in a multitude of ways.

Singapore’s Sleep Crisis Starts Young

Studies estimate that 65% of school-aged children in Singapore do not meet recommended sleep durations: 9.5 to 11.5 hours for primary schoolers, and 9 to 9.5 hours for secondary students. And as students get older, the problem deepens. By junior college, all-nighters become a rite of passage. Sleep becomes negotiable – optional, even — in the face of endless deadlines and expectations.

Culturally, we equate early rising and long hours with discipline and excellence. But neuroscience tells a different story: chronic sleep deprivation in youth is linked to memory deficits, impaired learning, emotional dysregulation, increased risk of depression, and long-term health issues like metabolic disorders and cardiovascular stress. With the rise in vaping culture, we should also be worried about the increased risk of substance use and abuse. That’s a hefty price to pay for academic success.

Why Later is Smarter

International sleep science bodies like the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that middle and high schools start no earlier than 8.30am. Singapore’s Ministry of Education, when asked in Parliament, revealed that only 1 in 10 secondary schools starts at 8am or later on at least three days a week. The only guideline is that schools start no earlier than 7.30am, but the ministry does not keep precise national records of school start times.

This isn’t just a policy oversight – it’s a missed opportunity. If we have the data to track exam scores and attendance rates, surely we can collect national data on something as fundamental as school start times and student rest.

On a smaller scale, a Duke-NUS study found that earlier class start times are correlated with significantly poorer sleep and academic performance among university students. Absenteeism, grogginess and diminished attention span were more common in early morning classes compared to afternoon ones.

In primary and secondary education, where attendance is compulsory and enforced, the absenteeism trend is less clear. However, we are still left with students who are not fully present in the classroom even if they are physically there at 8am. Surely, many of us are familiar with fighting every instinct to keep our eyes open in those early morning classes.

Well, you’re not alone. Neuroscientific studies have found that adolescents’ circadian rhythms (aka. body clocks) are shifted later than adults’. This shifting of circadian rhythms occurs during puberty, and is a well-documented phenomenon found across mammals. This means that adolescents naturally fall asleep and wake up later than adults, even with perfect sleep hygiene. It’s not just TikTok that’s to blame.

According to a study in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, this biological shift can lead to a loss of up to 2-3 hours of sleep every school day if start times are too early. Let’s consider the typical Singaporean secondary school student who gets 6.5 hours of sleep at night instead of the recommended 9. That’s 2.5 hours of sleep debt every night, adding up to 12.5 hours across the school week. By Friday, they’re functionally running on a full night’s sleep deficit. That’s neither trivial nor sustainable. The researchers even argue that a 7am school wake-up for a teenager is physiologically equivalent to waking a 50-year-old at 4.30am.

This isn’t about laziness or discipline. It’s biology. Young people’s internal clocks are programmed to sleep and wake later. But the current Singapore school system is not.

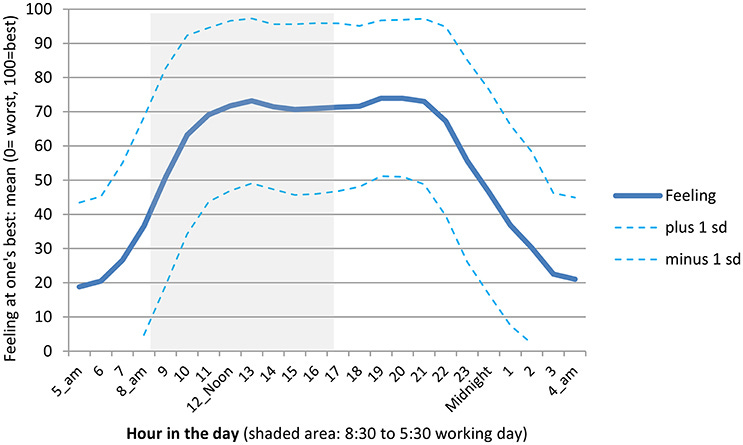

The study found that adolescents’ peak cognitive alertness occurs in the late morning, around 11am. That’s when working memory, attention and learning are at their sharpest. We design school timetables as though all hours of the day are equal, but they simply aren’t. 1 Simply put, we’ve created a mismatch between biology and scheduling.

Of course, it is unlikely we can push for 11am school start times despite how popular it would likely be among students. There are other factors to consider such as teacher working hours, classroom resources, alignment with parents’ schedules etc. However, small shifts yield big results, and the more sleep we give our youth, the more we optimise their learning outcomes.

Duration of Sleep Matters

A study conducted in a secondary school in Singapore found that delaying school start time by just 45 minutes increased total sleep by an average of 10 minutes per night, reduced daytime sleepiness and improved overall mood. That may sound small, but over the school week, it adds up to almost an hour extra of rest. Every little bit counts, especially in a culture where trading sleep for academic success is widespread.

Another similar study in the US found that a 1-hour delay in start time led to a two-percentile point increase in math scores. This is a stunning benefit and result, matching the effectiveness of costly teacher training, learning resources upgrading programmes, and at no cost.

Not only that, more sleep helps to break the vicious cycle that students fall into: sleep deprivation → sleepiness in class → poor academic performance → sleeping less/working more to catch up → more sleep deprivation.

Notably, these changes in school start times led to changes in total sleep time at night. Napping is a common workaround, but it doesn’t restore sleep debt the same way nighttime rest does. An extra 10 minutes of sleep at night is more valuable than a random 10 minute nap taken during the day, in between classes, hiding in the toilet cubicle to avoid getting caught. (Surely this is not just a personal experience??) In fact, compensatory naps can interfere with circadian rhythms, further degrading sleep quality. The key is not to patch over lost sleep, but to prevent it in the first place.

But Timing Isn’t Everything

Let’s be real: delaying school start times alone isn’t a silver bullet. If students are still spending 4-6 hours on CCAs, tuition, and homework after school, they’ll stay up just as late, and wake up just as tired.

The extra 10 minutes of sleep each night is valuable, but to inch closer towards the recommended durations, we need to interrogate deeper problems and inspire a cultural shift.

80% of primary school students receive private tuition, according to a 2015 Straits Times Survey. In 2023, the tutoring industry in Singapore grew to $1.8 billion. Access to tuition is also uneven — families with more means can afford help, while others feel pressured to catch up through even longer hours of self-study.

So many of our children are trapped in this culture of hustle. Fun and relaxation are seen as luxuries. Sleep is seen as weakness, and overwork as dedication. Students internalise this early, equating exhaustion with effort, and productivity with personal worth. It shouldn’t have to be this way. Students shouldn’t have to choose between rest and success.

To truly help our children, we must realise our role in shaping them.

MOE should treat this with the same rigour as any academic intervention: collect data, trial reforms, and measure outcomes. Schools can pilot staggered start times or flexible timetables, guided by neuroscience rather than tradition.

Parents can give students more unstructured time; deprioritise filling every hour of the day with excessive homework, tuition, enrichment classes etc. Practice good sleep hygiene and maintain a good work-life balance to set an example for the children.

We need to first recognise sleep as essential to both health and learning. Sleep is foundational. Without it, every other educational reform is built on sand.

Beyond School: A Nation of Exhausted Adults

These habits don’t end after graduation. Singapore is ranked the third-most sleep-deprived country globally. Just 1 in 4 adults here gets the recommended 7-9 hours of sleep a night. The LKY School of Public Policy has called it a public health crisis - and they’re right. Sleep deprivation doesn’t just kill productivity - it increases the risk of chronic illness, reduces resilience to stress, and deepens inequalities for those without flexible work schedules.

In a separate article we do a deep-dive into the sleep habits of Singaporean adults, and discover how sleep isn’t just an individual lifestyle choice – it’s also shaped by policy, social expectations and institutional timetables.

For now, the takeaway is that Singaporeans deserve to grow up rested, not burned out. Because a nation that dreams big needs to start by getting enough sleep to dream at all.

Evans, M. D. R., Kelley, J., & Kelley, J. (2017). Identifying the best times for cognitive performance using new methods: Matching university times to undergraduate chronotypes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00188