PPP(P): Politics, Prejudice, and the Population Panic

Unpacking the LGBTQ ‘Agenda’ Through Numbers, Not Noise

In Singapore’s recent presidential and general elections, a familiar scapegoat emerged. The LGBTQ+ people once again found themselves in political crosshairs.

In 2023, Presidential candidate Tan Kin Lian remarked ‘Diversity and differences shouldn’t be given too much attention. If you want to be a homosexual, do it privately. If you want to do it outwardly, then you actually cause problems with younger people.’

Meanwhile, during the 2025 General Election, the People’s Power Party ran on an openly anti-LGBTQ platform, warning against the so-called ‘LGBT agenda’ and blaming it for Singapore’s plummeting total fertility rate (TFR). Their run for Nee Soon GRC was even contingent on whether the incumbent party fielded a candidate supportive of LGBTQ rights - not even openly queer, just openly allied.

Why do these narratives always re-emerge during election season? Why is queer identity cast as a threat to national survival? Let’s unpack the argument - not through moral panic, but through math.

What is the TFR, and Why Does It Matter?

The Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is a statistical measure that estimates the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime. A TFR of 2.1 is generally considered to be the ‘replacement rate’ - the point at which a country’s population can sustain itself. This means that each couple produces two children to replace themselves in the population. Anything significantly below this rate signals a shrinking population, absent of immigration.

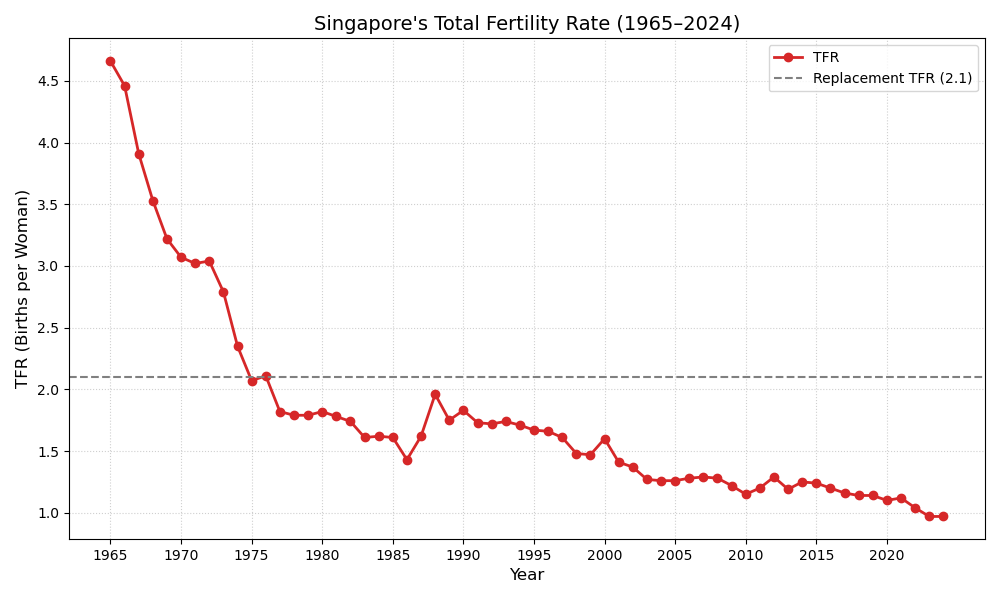

Singapore’s TFR has been below replacement level since the 1970s. In 2023, it fell to a record low of 0.97. Even the fabled ‘dragon year’ effect - which previously sparked spikes in birth rates due to cultural beliefs about the auspiciousness of the dragon zodiac - failed to lift the numbers in 2024.

In 1980, the age group with the highest fertility rate was 25-29. By 2024, it had shifted to 30-34. This delay in childbirth correlates with rising educational attainment among women, increased participation in the workforce, and changing social norms around marriage and family.

What’s Really Behind the Decline?

Falling fertility rates are not unique to Singapore - they’re a hallmark of almost every developed economy. In our case, long BTO wait times, high childcare costs, long working hours, and skyrocketing living expenses only exacerbate the issue.

Singapore once even ran an active birth-control campaign - ‘Stop at Two’ - from 1972 to 1987. By the late 1980s, it reversed course, pivoting to pro-natalist policies in response to declining birth rates. We’ve tried it all. But fertility is not a simple lever we can pull at will. It’s a complex social outcome, shaped by everything from economic pressures to gender norms. You can’t tweak it to match shifting political agendas and expect predictable results.

Even if every queer person turned straight…

Let’s test the claim: that the LGBTQ community is to blame for our low TFR.

We estimate that 3% of Singapore’s population identifies as queer, based on the 2021 UK census (Singapore does not yet collect orientation-specific census data). Now, suppose every queer person became straight and had children at the same rate as current straight Singaporeans. What would happen?

Assuming that 97% of the population, the straight-identifying group, produces all the current fertility, this means that they have a TFR of 1.00.

If queer Singaporeans suddenly began having children at the same rate, the national TFR would only rise from 0.97 to 1.00. That’s a mere 3% increase, and still less than half the replacement rate. For queer couples to single-handedly close the gap, each would need to average over 37 children. That’s obviously absurd. The problem clearly doesn’t lie with the gays - and the solution doesn’t lie with taking their rights away.

Besides, the assumption that LGBTQ people don’t raise children is simply false. Many already do, within heterosexual-presenting marriages, through adoption, surrogacy, or co-parenting. Many more want children and families of their own.

And anyways, what was the plan? Handmaid’s Tale your way into making queer people procreate?

What ‘Agenda’ sia?

One of the most notable milestones in Singapore’s LGBTQ history was the 2022 repeal of Section 377A - the colonial-era law that criminalised sex between men. The UK repealed a similar law in 1967; other ex-colonies like India did so in 2018. Singapore’s repeal came after years of advocacy, but with the cost of a constitutional amendment to reinforce the definition of family as between a man and woman.

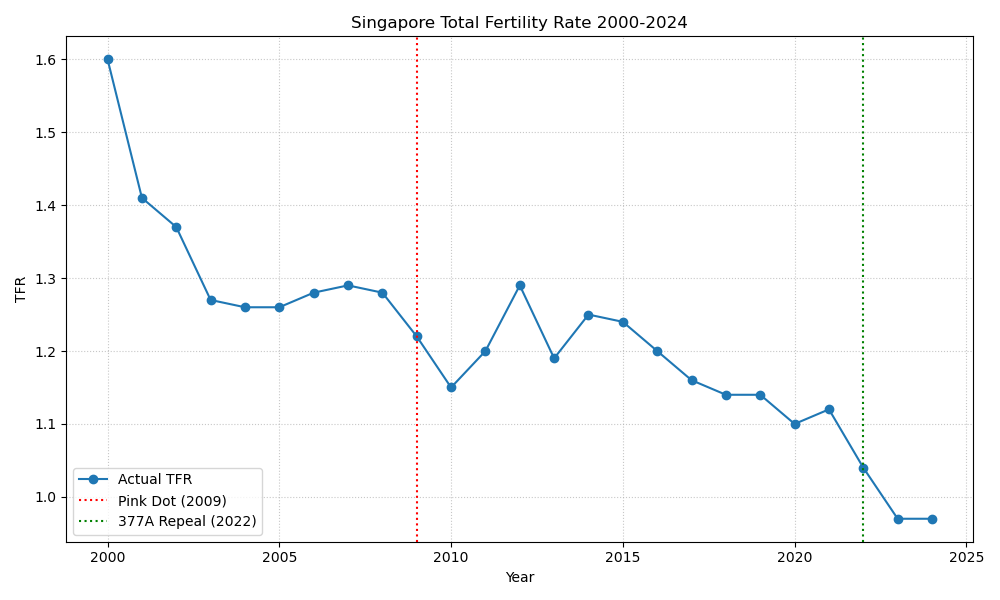

Critics have warned of moral collapse and societal breakdown after this repeal. But the numbers simply don’t support this claim. TFR trends post-2022 show no statistically-significant deviation from the long-term linear decline that began decades prior. The same holds true post-2009 - the year Pink Dot, Singapore’s now-annual pride event, launched. These milestones didn’t break the nation. They barely nudged the fertility curve. 1

Where is this catastrophe that we were warned about?

A Global Perspective

Singapore has yet to legalise same-sex marriage, and public pushback remains common, especially among certain demographics. So let’s look abroad. What happened to fertility in countries that did legalise it?

Denmark, the Netherlands and France saw an increase their TFRs after legalising same-sex marriage. Argentina and Hungary saw declines instead. There is no consistent or clear trend of a fertility crash following LGBTQ-inclusive reforms.

In Singapore, queer couples are still denied access to adoption and family-building rights. The real policy gap isn’t that the LGBTQ agenda is harming the family unit - it’s that the state refuses to support the loving, stable families that do not conform to the traditional narrow mold. And that hurts everyone. Single mothers, multigenerational households, couples relying on IVF, who all exist here, would also benefit from a more expansive, inclusive definition of parenthood. Inclusive policies will add more children to loving homes, not fewer.

The Myth of the Traditional Family

Other than the TFR argument, much of the anti-LGBTQ rhetoric hinges on preserving ‘traditional family values’. But what exactly is this tradition we’re trying to defend?

The nuclear family - dad, mum, and 2 kids in a HDB flat - isn’t some timeless ideal. It is a post-industrial construct, reinforced during the 1960s-80s in Singapore as part of nation-building efforts. But families in East and Southeast Asia were historically far more fluid: intergenerational, extended, adoptive, communal. And yes, even queer.

Take the Sida-Sida, the androgynous Malay priests of 15th-century Meleka, often reported to participate in same-sex relationships. Are they not ‘traditional’ too?

Across history, queer individuals have found ways to build families. They still do. If we genuinely want to protect social cohesion and family values, the answer is not to limit our definition of the family. It’s to expand it.

Social Harmony Where?

If we are worried about social harmony, let’s examine the actual behaviour of some politicians stoking this panic. Tan Kin Lian, the same candidate blaming queer people for moral decay, faced backlash over his objectifying posts about underage girls. A former PPP member was arrested for road rage. These are not hypothetical harms - they’re real, visible and unaddressed - caused by the very voices calling for a societal return to moral purity. This obsession with imagined threats only distracts us from fixing actual societal problems.

The Data Has Spoken:

There is no evidence - mathematical, sociological or historical - that the LGBTQ community is to blame for Singapore’s low fertility rate. The numbers don’t lie, but politicians often do.

Blaming queer people is not just lazy politics. It is dangerous, harmful and unsupported by any serious analysis. It diverts attention from the real challenges: economic and gender inequality, parental support and social infrastructure. And it harms us all, not just the LGBTQ community. Declining birth rates, toxic masculinity, incel culture, loneliness epidemics are the symptoms of a society that has failed to adapt. Demonising queer people will not fix them. We’re not saying a falling TFR is inherently bad. But if we’re trying to raise it, the solutions lie in equity, affordability, and inclusive policy - not scapegoating.

Singapore deserves better than fear-mongering. We deserve leadership grounded in fact, not phobia.

Singapore Department of Statistics. (2023). Births And Fertility Rates, Annual (2025) [Dataset]. data.gov.sg. Retrieved July 6, 2025 from https://data.gov.sg/datasets/d_e39eeaeadb571c0d0725ef1eec48d166/view